Links to other sites are highlighted in red. Conditions of site use are at the end of this page.

Clicking a numbered reference takes you to Notes on a new tab. Scroll down to the note in question.

You could also view Journal and Notes simultaneously on separate displays.

Read about Henry's ship, the Robert Lowe. Comments are welcomed.

Robert Cutts, bob@winton.me.uk.

Clicking a numbered reference takes you to Notes on a new tab. Scroll down to the note in question.

You could also view Journal and Notes simultaneously on separate displays.

Read about Henry's ship, the Robert Lowe. Comments are welcomed.

Robert Cutts, bob@winton.me.uk.

|

| Advertisement in The Times, 30 June 1862 |

The Journal of Henry Taylor

being an authentic diary kept by my great grandfather, Henry Taylor, during

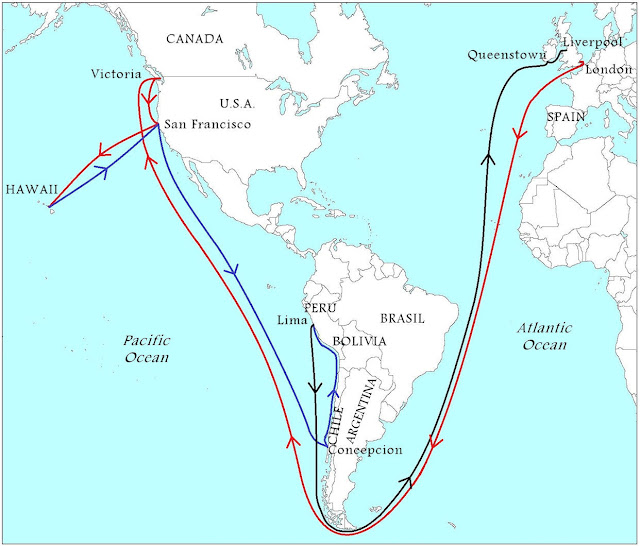

his journeys through the Americas from September 1862 to January 1867

About the months of July and August 1862 I read many accounts of the immense wealth of the newly-discovered Gold Fields of British Columbia and became dissatisfied with my position and prospects. I was then a Clerk in the employ of Hepworth and Co, Princess Street, Manchester. The exaggerated reports of the extreme amount of gold which had been taken out of the Caribou during the season of 1861 so excited my almost dormant spirits that I longed to exchange the monotony of a counting house life for the wild and uncertain life of a miner. It is true I was but a boy, "only nineteen years old" they said, and my constitution little calculated for the wear and tear of such a change as I proposed to make. But my mind was made up to leave England, home and all their many happy associations the value of which I could never learn until estranged from them by residence in foreign climes.

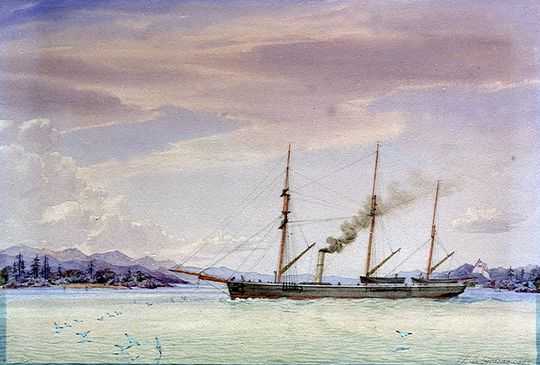

The SS Robert Lowe c1856

Please acknowledge the museum if you embed this image in your website.

Please do not download the image. The artist is unknown.

|

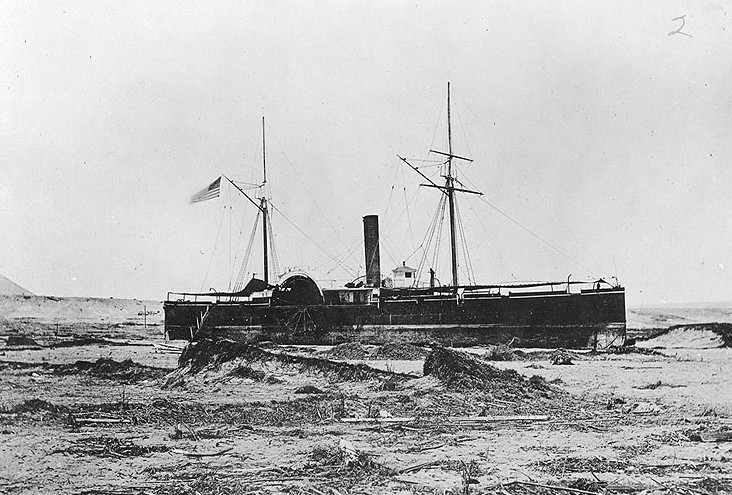

| 'Iron Cross' in c1875 – the ship that was originally named 'Robert Lowe' (The Malcolm Brodie collection of the State Library of Victoria, Australia) |

I took passage on the steamship "Robert Lowe1", 1478 tons and 300 horse power, and sailed from Shadwell Basin, London Docks, at 3.00 pm on the ever memorable 15th of September. It was at that hour that the most bitter pang of parting was felt by all those who were leaving behind them those more or less dear ones. The parting with my dear Mother, who stood on the dock lost in tears and fearful anxiety for my future welfare, was indeed a severe one. My mind was almost changed and I was half inclined to retrace my steps ere it was too late, but the thoughts of the ridicule I should incur and the dread of again returning to the drudgery of a desk prompted me to go. And go I did. May the Great Ruler of the Universe be pleased in his infinite mercy to spare my dear Mother to see the return of her only son.

September 15th 1862

|

| Gravesend in 1839, Samuel Walters |

|

| Henry dreaming! |

Being an inexperienced traveller, the idea of sleeping in a miserable bunk of wood, along with some seventy others, was anything but pleasant. Nevertheless I slept and dreamt of nuggets of gold in a homeward bound ship.

September 16th 1862

The rest of the passengers embarked. One of the steerage passengers changed his mind, sold out cheap – bag and baggage – and went ashore. He was laughed at, but who knew the motives that influenced his decision. Perhaps it would have been as well if many others of us had followed his example.

September 17th 1862

At 4.00 am we left Gravesend with a pilot aboard and proceeded about 25 miles down the river when we met with a slight accident to our screw and were obliged to return to repair the damage. Our Chief Engineer went ashore in the steam tug and returned with one of that amphibious race, a diver. I then had the opportunity of witnessing for the first time the modus operandi of this strange individual. He remained below for 14 minutes making observations. What he reported when he came on deck, I was unable to ascertain, beyond that it was necessary for him to go down again next day.

September 18th 1862

The diver went down again and completed the repairs after which we left Gravesend once again.

September 19th 1862

September 19th 1862

|

| The Albion Cliffs, Dover |

We passed the Albion Cliffs of Dover and about 9.00 pm we saw the lights in the town very distinctly.

September 20th 1862

On going on the deck in the early morning we found that we were out of sight of land.

September 21st 1862, Sunday

We mustered on the quarterdeck and a service was performed by our fellow passenger, the Rev Mr Reese2; He, along with his wife, had taken passage with the intention of establishing an educational college in Victoria. Oh! How imposing was this service and how familiar to almost everyone on board. What deep reveries it caused us to fall into and how many happy Sundays were remembered when, in the company of those near and dear to us, we had united in Praise and Prayer in the Sanctuaries of "Dear Old England."

Until today we have had really glorious weather, a smooth sea and no rain, but the elements of wind and rain seem only to have been caging up their violence to unite in one fearful outbreak and now, for the first time, the dreadful effects of going to sea are visible on every hand. "All hands and the cook" are sick. It is true that some of the lucky ones escaped, but Neptune is a hard toll collector and very few can cross his path without paying him his due! It is a most disgusting sight. And how those cruel sailors did tease us poor land lubbers: "Wait a minute – we'll put you ashore in the long boat!", "Aren't you sorry you came to sea!", "Hurrah for Caribou!" and similar consolation was all we got out of them. I held out bravely until evening when I found it was indispensably necessary that I should "give way to my feelings" to use a very mild form.

September 22nd 1862

The weather was little or no better. The greasy pea soup was not sufficiently tempting to my appetite, so I was obliged to go with a very empty stomach, much to my disgust.

September 23rd 1862

When I awoke I felt hungry and dived eagerly after some of the little delicacies I had brought from home and during the rest of the day I felt tolerably well. My bout was comparatively short, seeing that some of my fellow passengers were sick for more than a month.

October to December 1862

|

| A concert on deck |

To the rest of the voyage little or no interest can be attached, unless indeed monotony is interesting. We had on board some good amateur singers and it was the custom, in fine weather, to hold concerts on deck. Such social meetings were bright oases in the great desert of our four months' voyage. Enjoying them we could shut our eyes to the past, to the future, to our dangerous position, thousands of miles from land, the fathomless ocean beneath us. All were forgotten. What mattered it to us that we were all portionless adventurers seeking the wherewithal to make life's closing years not only endurable but happy. Many of us remembered an old song which I had often sang with my dear father:

High feasting makes us earthly,

Nor ever helps us rise.

Deep drinking drowns the spirit,

And keeps us from the skies.

Loud mirth is false and hollow,

Nor makes us happy long.

But would a man be merry

Why, let him sing a song.3

Boxing gloves and sword sticks were in great demand for a while but, getting out of order, had to be laid aside long before the termination of the voyage.

We had aboard as cabin passengers a Mr Wood4, his wife and two grown up daughters, the younger of whom – Miss Ellen – was considered the most handsome and accomplished young lady aboard. Possessing such attractions as were hers, and shining with such bright effulgence as she did, in a community which was debarred from the ordinary social intercourse of life at home, it was not remarkable that she should have admirers. Amongst such were two lower deck passengers one Frank Passingham and the other "Garibaldi" Thompson, as he was familiarly called to distinguish him from two others of the same name that were with us in the steerage.

Garibaldi was a man of an age which it would be unsafe to surmise. However, according to his own account, he had held a commission under General Garibaldi in the Italian Campaign – hence his nick name. He said he had performed many valorous deeds to aid in rescuing Italy from her tyrannical oppressor. In spite of all this he was generally considered to be slightly deranged in his upper story. Passingham was a youth of some eighteen years, possessing hair of such a brilliant hue as to gain himself the very significant cognomen of "Carrots". He was tolerably witty and considered more than ordinarily intelligent.

It was arranged between the friends of Passingham and those of Thompson that the latter should write to the former a letter demanding a surrender of all claims to the affections of the young lady in question or a choice of weapons! In reply Passingham most peremptorily refused the first request and went on to mention the name of his "Friend" whom he said would make arrangements to bring about a mutual settlement of the affair with the aid of a brace of persuaders in the shape of single barrelled pistols! Seconds were chosen and it was arranged that the "little meeting" should take place on the forecastle at 5.00 am. In the month of; December and in the vicinity of Cape Horn, we could only expect it to be pitch dark at the hour indicated.

Punctual to the minute, the rival lovers met amid the cheers of eighty sleepy mortals who were eager for the fray. It would not be out of place here to mention that it was arranged between the seconds that nothing but blank cartridges should be used. At the same time Thompson was kept in happy ignorance of this fact.

Ten paces were measured and the word was given.

Thompson turned deadly pale as, after his shot, he saw his antagonist fall – pierced, as he thought, to the very heart.

When a young medical student, Dr Brown, pronounced with greatest gravity that the wound was mortal and that the patient could not possible survive, visions of being placed in irons in the main hold, with a diet of bread and water and a pallet of straw followed by a trial and Sentence of Death on reaching Victoria, all passed rapidly through Thompson's much excited brain.

The report of the pistols had brought on deck, en dishabille [in their underwear], the Captain and several of the After Passengers. Of course the ball was up, and when the cause of the affair became known in the cabin, Miss Ellen, who bye the bye had never exchanged a sentence with either of the "Duellists", blushed and declared her approval of the brave manner in which "Mr Thompson" had endeavoured to maintain his imaginary right to her hand.

Ever after this occurrence, poor Thompson was made the butt of ridicule and the subject of almost every practical joke. On arriving in Victoria he commenced keeping school but, not meeting with much encouragement, gave way to despondency and, poor fellow, was found one morning suspended by his braces to the beam across his humble dwelling a stiff, discoloured corpse5.

Every Sunday we had Divine Service on the quarterdeck in fine weather or, when unfavourable, in the saloon.

Among our "precious" freight were 36 Female Emigrants from Lancashire – sent by the Emigration Society in London6. They were during the passage kept under the strict surveillance of the Captain, the Surgeon and our Minister. They were not allowed to associate themselves with any of the male passengers. On our arrival in Victoria, they were properly cared for until places suitable to their abilities could be procured. Within a week they were all at work. Afterwards some of them married well – much better than they could have been expected to do had they remained in England.

|

| Sea Captain by Yoo, Choong-Yeul |

Our Captain, Mr Congalton7, we found to be a very fine man. Though entertaining rather aristocratic notions, he was ever ready to hear any complaints the passengers might have to make, and he was always willing to give us the full benefit our position entitled us to. We had every confidence in his ability as a skilful seaman for, more than once, we had the opportunity of seeing that he knew what he was about. He could keep cool in moments of the most imminent danger for, although the passage was on the whole a pleasant one, we had several severe gales and squalls during which we often did on our knees commend ourselves to Him who holdeth the winds in His hands and who rules the vast oceans as well as the Earth.

|

| Under the Mast |

When our gallant craft was tossed like a cork upon the bosom of the mighty deep, when the winds howled through the shrouds, the waves washed mountains high "till with the hurly, Death itself awoke" – then was it that we felt our utter dependence on God.

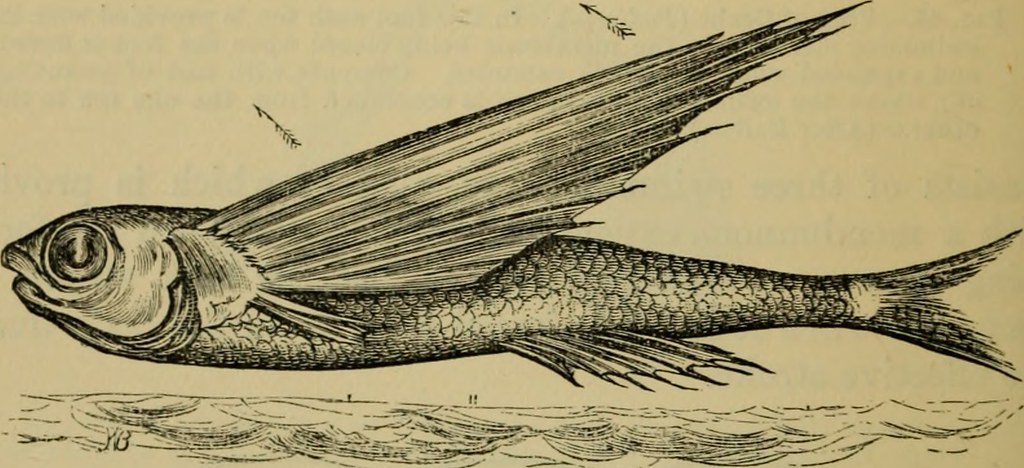

We saw large shoals of whales, porpoises, blackfish, grampuses and flying fish. We managed to harpoon one porpoise from the jib boom. The flesh was cooked and, as a change, was anything but disagreeable to the palate.

Coming round the dangerous Cape Horn we were accompanied for a week by numbers of Cape Hens and Cape Chickens, whose presence somewhat relieved the dull monotony of sea and sky. During the voyage we sighted Madeira, the Canary Islands, Staten Island [off Cape Horn] and Pernambuco [a province of NE Brazil].

| 1762 map of the Strait of Magellan and Tierra Del Fuego by Emmanuel Bown Staten Island (Isla de Los Estados) is on the right (Victory Adventure Expeditions) |

The magnificent sunsets, to be seen only in the tropics, were the subject of wonder and admiration. Had an artist in England painted scenes of such grandeur, displaying such gorgeous colours and such remarkable combinations of effects, those who had never seen such scenes would have accused him of over-exercising his imagination. Nevertheless how we longed for the powers of an artist to transfer these glorious sights to canvas!

In the latitudes of Cape Horn no amount of clothing was too much. We could pile coat upon coat and still call for more. The days were dark and gloomy and, although it was the Summer of the Cape, we were for weeks without a glimpse of either Sun or Moon.

Christmas Day was, as with Englishmen everywhere, a great day. On that day we feasted ourselves on fresh beef, procured from the flesh of a poor consumptive old cow which was so far gone as to render it a mercy that she should be massacred. That tough pound of beef was far more acceptable to us than a fine old English Christmas Dinner at home. We did our best to be happy and to spend a "Merry Christmas" but our thoughts would inevitably fly back to the firesides of the homes we had left so far behind.

January 8th 1863

|

| The Cape Flattery Light (NOAA's Sanctuaries Collection via Wikimedia) |

At 2.00 am we sighted the Light House of Cape Flattery and the same day entered the Straits of "Juan de Fuca"8.

What a sight for us "Britishers"! On each side of the straits, towering almost to Heaven, cloud capped mountains covered with snow met our admiring gaze. Forests of pine and the huts of the native Indians were also visible and were objects of great interest to us. It was then that we began to speculate on the prospects before us. Our long dormant energies were awakened and the reality of our position was fully realized by every one.

|

| HMS Topaze in the 1860s (Hastings, George Fowler collection via Wikimedia) |

January 11th 1863 (Sunday)

Few of us slept much during the previous night for we were anxious to catch a glimpse of the harbour in which we were so snugly moored. When daylight came we were, to our relief, much gratified by the sight. It would be useless for me to try to describe the beautiful harbour and the magnificent scenery surrounding us. It is said to be one of the grandest sights of the Pacific. The water was smooth as a mirror for not a breath of breeze disturbed its surface. The only sounds which greeted our ears were the sharp shrill cries of the hundreds of wild duck and other birds watching very intently for any scraps of bread that might be thrown overboard and the jabberings of the Indians in their canoes alongside, using their utmost endeavour to supply everyone aboard with a large stock of fish.

|

| Henry Taylor's Journal – reaching Victoria |

Being Sunday, it was of course necessary that we should wait until the following day to be transported en masse to Victoria11. A number of us decided upon going ashore and walking to Victoria – a distance by land of about five miles. Accordingly a party of about twenty of us started on an exploring expedition and, after a long walk over a rough, half finished road, we reached the capital of Vancouver Island. We found it in a very dirty condition and had great difficulty in making headway through the streets, which were literally ankle deep in mud. Instead of pavements of flag or stone, they just have wooden side walks, and these were in such a fearfully dilapidated condition as to render them quite dangerous.

[The passenger list of the Robert Lowe is at the end of the Journal].

|

| Victoria in the mid 19th century (From the Islander) |

With very few exceptions, the buildings of the city are constructed from wood. The St Nicholas Hotel, Government Street, and the bank of the British North America are the largest brick and stone buildings on the Island. We found several good wharves, all built on piles driven into the bay. The largest of these belong to the Hudson's Bay Co who, bye the bye, are the largest and most influential people on the colony. The Governor of the Island, Sir James Douglas, resides near Government House. He is a man much respected, both by natives and foreigners.

| Indian Camp at Fort Colville, Washington Territory Painting by Paul Kane c1860 (Wikimedia) |

Outside the town are many Indian Encampments. Most of the natives prefer the natural wild mode of life to that of a few of their tribe who, becoming a little civilized, have bought or rented shanties in town. Their language is a strange gibberish composed of a mixture of English, French and Indian words. It is easy enough to learn and to pronounce, but the critters, as they are called, seem to have a decided objection to learning English. They manufacture matting, baskets, small canoes and the like. They peddle their wares through the streets and thereby make a little money wherewith to purchase some of the little delicacies more familiar to their white neighbours. They are, as a general thing, exceedingly filthy and lazy in the extreme. The mode adopted by their women for carrying their offspring is perhaps a pleasanter one than the one used by Europeans, if not quite so elegant. They strap them tightly on their backs, or carry them in a basket fastened on their backs by strong cords, thus leaving both the arms of the mother at liberty.

|

| Theatre Royal, Victoria in the 1860s (Victoria's Victoria) |

There are many restaurants and drinking saloons in the City. It is a fact that impresses itself at once on the mind of every one arriving from the old country, that the colonists patronise this class of place much more than the people at home. There is also a theatre here, but I am sorry to say that the patronage of Europeans and Americans is of so little account that it will pay no manager to keep a good company. However, the Indians, both Siwash and Klootchman12, may be found there nightly. Though able to understand hardly a word of the dialogue, they love the gaudy dresses. Their taste in this line almost amounts to monomania. They may be found in the streets with an old red blanket thrown around their heads, adorned by an old hat, once the possession of a sailor or soldier, now stuck full with coloured plumes. For a pair of red pants or a soldier's jacket they will do anything, with the exception perhaps of washing themselves or combing their hair. To these occupations they entertain an almost religious aversion.

As my stock of finance was rather limited, I began to look out for an occupation and at last got something. It hardly enabled me to live the life I was accustomed to at home, but I betook myself to it as cheerfully as possible. I was hired at $1.25 a day, board not included, to work at road making about four miles out of town on the Saanich Road. We had a tent of fir boughs to sleep in (and on!) and a large log fire in front, to cook by. This was pretty rough in the depth of winter, with snow four or five inches thick on the ground and the water covered with ice. I stayed at that till we got clean frozen out and the work had to be stopped. Returning to town I managed to obtain a situation as assistant bookkeeper with J G Little in the Wood and Coal business.

March 23rd 1863

I sailed in the Adelaide Cooper13 for Port Ludlow14, Puget Sound in Washington Territory. The Captain of the barque was a Mr. Dingley. The voyage took five days. We first crossed the Straits to Port Angelos [sic] and, thirty miles on arrived at Port Townsend, a miserable apology for a town.

|

| Port Townsend in the 1860s (HistoryLink.org) |

At that point we entered Puget Sound and thirty miles further on we came at last to Ludlow. This place is on a spit – a small projection of land. It is occupied almost solely by a sawmill where some seventy hands are employed. They daily manufacture lumber, which is shipped to California, China and Australia. I went to work in the mill of Amos Phinney and Co at $50 per month, with board. Tending the bar at the Hotel, I found Harry D Thompson, a comedian who I had often seen at the Theatre Royal, Manchester. He is the brother of Miss Lydia Thompson of the Lyceum Theatre15, London.

May 6th 1863

Went to Port Gambol (sic) in the schooner “Black Hawk”.

May 9th 1863

Returned to Ludlow in a canoe with two Indians.

On entering the Straits of Juan de Fuca from the open Pacific we leave the revolving light at Cape Flattery on the right-hand side. The shores of Vancouver’s Island on one side and Washington Territory on the other are visible. On the American side we see nothing for miles but snow-capped mountains. Chief amongst these stands Mount Baker, the summit of which is covered with perpetual snow. Gradually, as we proceed up the straits, the landscape unfolds itself. The various undulations then revel themselves as being immense forests of fir and maple. On the British side we see no snow-clad hills but dense masses of fir so thickly set that we wonder how it is possible for them to grow. We see on neither side any signs of human habitation for upwards of 100 miles from the lighthouse at Cape Flattery.

Next we come to Race Rocks with another beacon. Next comes Esquimalt Harbor, with H.M. Frigate “Topaze” and the gunboats “Grappler”, “Devastation” and “Forward”. Seven miles further on we come to Victoria Harbor. But as there is no safe anchorage for large vessels here, it is mostly used for smaller craft.

|

| H.M.S. Grappler (University of Victoria) |

We next leave the straits and come to Puget Sound, the Custom House at Port Angelos. 25 miles higher up is Port Townsend, a miserable apology for either city, town or village. 35 miles more and we reach Port Ludlow where I staid [common 19th-century spelling of stayed] for some time. This place is called a “spit”. It is a small projection of land occupied almost solely by a sawmill where some 70 hands are employed daily manufacturing lumber which is shipped to California, China and Australia.

|

| The Custom House at Port Angeles in 1910 (Flickr, James Wengler) |

A few miles from the mill, just across the narrow sound, I visited an Indian Burial Ground, a sight of considerable interest. Here, raised some six or seven feet from the ground on slender trees, are suspended old dry goods boxes, containing the last mortal remains of many a Chinook Chief. The bodies are doubled up and wrapped around with old matting before being enclosed in the rude boxes. Suspended round these singular sepulchers are old blankets and clothes formerly used by the deceased. On the tops of the boxes are the tin plates, pannikins, fishing lines and other articles formerly used by them.

| The Pope & Talbot, Inc. Sawmill Site in 2011 (Washington State Department of Ecology) |

|

| The same sawmill in the 1860s (HistoryLink.org) |

The other ports in the vicinity are Olympia, Utsalady, Siebec, Steilicoom, Discovery, Madison and Thompson.

The scenery of the Sound generally is strangely wild and singularly picturesque. Strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, gooseberries and currants abound in large quantities. Wild flowers and unusual ferns are also abundant.

Resumé

June 21st 1863

Left Port Ludlow for San Francisco, California, in the barque Adelaide Cooper with 250 lengths of lumber and two large spars. I had shipped to work my passage before the mast. We anchored at Port Townsend the same evening.

June 24th 1863

Cleared Cape Flattery and, after a pretty rough passage of fifteen days, on July 5th we anchored in 45 fathoms in San Francisco Bay.

On the following day we landed and I took up abode at Pacific Temperance House, Pacific Street.

July 9th 1863

August 15th 1863

Sailed upstream for Antioch on the steamer Cornelia. I went to sleep during the passage and did not wake up until after we had passed my proposed destination.

Landed at Stockton at midnight. Left on the same boat at 4 pm with Brigadier General Connor, bound for Salt Lake City, on board. Arrived at Antioch at 9.00 pm and took stage to G H Hammon’s at Pittsburg, Contra Costa.

September 8th 1863

|

| The Paddle-Steamer, Helen Hensley (MacMullen, Jerry, Paddle-Wheel Days in California, Stanford Univ Press, 1944 via Wikimedia) |

Returned to San Francisco on the steamer “Helen Hensley”.

November 18th 1863

Left San Francisco on the schooner "Louisa Harker" bound for Vallejo, Solano County, across the San Pablo Bay.

November 19th 1863

|

| Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley |

Arrived at Vallejo Steamboat Landing at 5.00pm.

November 30th 1863

Was introduced George Edgar16, a cockney, whom I afterwards found to be a perfect gentleman. He keeps the largest and most respectable saloon in town and is highly respected by everyone who knows him. Went to work for him as a bar keeper and had a very good situation of it while the Russian Fleet of five vessels was lying at Mare Island Naval Yard.

December 23rd 1863

Attended a performance by the Amateur Dramatic Club of "Charcoal Burner" and "Rough Diamond".

February 3rd 1864

Wrote Mr. Briggs.

February 4th 1864

February 3rd 1864

Wrote Mr. Briggs.

February 4th 1864

Left Mr Edgar's employ and commenced ranching with Mr T J Johnston, a very fine fellow belonging to Virginia.

[On March 11th, though not reported by Henry, there was a slight earthquake in the City at 9:15 A.M. A portent, perhaps, of what was to come 18 months later].

[On March 11th, though not reported by Henry, there was a slight earthquake in the City at 9:15 A.M. A portent, perhaps, of what was to come 18 months later].

April 23rd 1864

Left the ranch and went to ship-keepers mess on Mare Island.

[On May 20th though again not reported by Henry – maybe because he was away from the City – there was another earthquake during the day with very severe shocks, causing people to rush into the streets].

May 21st 1864

Returned to the City on the Steamer Amelia.

May 23rd 1864

Went with one Dick Brashears to Crystal Spring Hotel, which is kept by a Yankee named Tony Oakes.

June 6th 1864

Returned by stage trail to the City.

June 13th 1864

Took service on ship for six months as Officers' Steward on the U.S. Surveying Cutter17 William and Mary.

June 29th 1864

Got under way on at 1.00 pm, arriving in Mare Island at 5.00 pm.

July 1st 1864

Left at 1.00 pm on July 1st and anchored at Steamboat Point at 6.00 pm the same day.

July 1st 1864

Left at 1.00 pm on July 1st and anchored at Steamboat Point at 6.00 pm the same day.

|

| Mission Bay map drawn By V. Wackenreuder, C.E. 1861. (Published by Henry G. Langley for the San Francisco Directory) |

Mission Bay was on the City's eastern shore just south of where the Bay Bridge is now. Note that, unlike modern maps, north is on the right and west is at the top. Even by the 1860s, Steamboat Point was no longer a point as the part of Mission Bay to its west had been in-filled. The original shoreline is shown on the map. The in-filling continued until Mission Bay disappeared altogether. In the mid 1930s the Bay Bridge was built. It spans San Francisco Bay west to east from Rincon Point to Oakland (City and County of San Francisco. Compiled from Official Surveys and sectionalized in accordance with U.S. Surveys.

|

| Mission Bay, San Francisco in the 1860s (designbythebay.com) |

July 4th (Independence Day)

Fired a salute of 21 guns at noon.

August 4th 1864

Left for Suison at 10.30pm. In San Francisco Bay, sighted the steam frigate “Devastation”, the Russian flagship “Bogatyre”, “Admiral Popoff” and several French men of war, colours dipped.

August 22nd 1864

Left at 8.00am. Becalmed at noon and anchored near Mare Island.

August 24th 1864

We got under way on the following day, arriving in San Francisco at noon. At 3.00 pm set sail again and anchored off Point Penola [Pinole Point on the above map] for a day's surveying.

August 24th 1864

Returned to Suison Bay, dropping anchor there at 6.00 pm near the brig “Fauntleroy”.

August 31st 1864

Left at 2.00pm anchoring at the Navy Yard at 6.00 pm.

September 2nd 1864

Left Mare Island at 1pm and anchored near San Quentin Prison at 7.30pm

September 3rd 1864

|

Maguire's Opera House, Washington Street, San Francisco in 1869

(Courtesy of Museum of Performance and Design, Performing Arts Library)

|

Got under way and anchored at South Park at 8am. In the evening went to Maguire's Opera House and saw Mrs H A Perry as Mazeppa.

September 14th 1864

|

| Maguire's Academy of Music in the 1860s (Online archive of California) |

Heard the opera “The Bohemian Girl” at Maguire's Academy of Music with Riching's Opera Troupe with H. C. Peakes, bass, Miss Caroline Richings and Miss Kate Martin the principal vocalists.

September 20th 1864

Got under way at noon and anchored off North Beach at 4pm.

September 27th 1864

Got under way at 11am.

September 28th 1864

|

| Half Moon Bay, California in 2009 (Wikimedia) |

Anchored in Half Moon Bay at 11am. During our stay here I had some good fishing as tomcods, flounders and the like abound. Also I shot several seals. Went ashore twice and visited the ranch of a Mr Dennison where there were several modern agricultural steam implements. The farm hands were native Californians and Mexicans.

October 7th 1864

Left at 1pm. We were off the Heads in a fog all night.

October 8th 1864

|

| ||||

Anchored off Pacific Street Wharf at 3pm. In the evening saw Mr and Mrs Chas Kean at the Opera House in “Henry 8th”

October 11th 1864

October 11th 1864

Got under way at 11am and anchored at Mare Island Navy Yard at 5.30pm.

October 13th 1864

Left at 8.30am and anchored off Mission Creek at 8.30pm.

October 17th 1864

Saw Mr and Mrs Kean in “The Merchant of Venice”.

October 25th 1864

Went to Mr Richings benefit at the Academy of Music to see the Druids' Scene from “Norma”, a comic opera called “The Doctor of Alacantara” and a "Grand Tableau of Washington" with the “Star Spangled Banner” sung magnificently by the whole company.

October 31st 1864

Spent a very pleasant evening at a party given by Mrs Campbell of Third Street.

November 1st 1864

Went to Miss Riching's Benefit at the Academy to see “The Daughter of the Regiment”.

November 14th 1864

The “Comanche”, the first Monitor built on the Pacific Coast was successfully launched. As we lay close to, we fired a salute of five guns. The Hon J P Buckley18 met with a fatal accident during the launch.

November 24th 1864

This is the annual Thanksgiving Day of the American Nation. It is observed here in the same way that Englishmen keep Christmas Day at home – with Family Dinners and evening parties everywhere.

November 29th 1864

Left at 10.30am and anchored at Mare Island at 2.45pm. The U.S. Steamer “Wateree” is undergoing repairs in the dry dock [The repairs to "Wateree" are alluded to in Wikipedia. The ship turned up again when Henry reached Callao].

December 3rd 1864

Got under way at 7am

December 4th 1864

Anchored at Steamboat Point at 2pm

December 23rd 1864

|

Montgomery Street, San Francisco, in 1866 viewed from the Eureka Theatre |

December 28th 1864

Left the “William and Mary”.

December 29th 1864

Saw Miss Fanny Brown at the Academy in Pretty Girls at Stillberg.

December 30th 1864

Saw the Pantomime of “The Red Gnome” at Bert's New Idea with some of the best acrobatics I have seen – by Ross and Carlo.

January 1865

|

| The New York Clipper masthead |

Spent a month soliciting advertisements for “Clipper”19 and “Our Mazeppa”20.

February 13th 1865

Went to Talbot's21 benefit at the Academy. Heard a pretty good minstrel performance and saw Talbot shoot an apple from the head of a young lady at twenty paces using a pistol. On the following day I met two of my fellow passengers from the Robert Lowe – Winter and Mason from the Cariboo and Washoe mines.

February 15th 1865

Spent the evening at Worrell's Olympic.

February 22nd 1865

Shipped as Cook and Steward on the Hawaiian Brig “Nuuanu” captained by Mr Hugui for the Hawaii (or Sandwich Islands).

February 24th 1865

Set sail at noon and the pilot left at 2pm. Had fair and light winds for the whole passage.

Sighted the most southern of the Hawaiian Islands and, during the rest of the day, passed through several others of the group.

Sighted the Port of Honolulu at 9am and at 10am a pilot and a Kanaka crew came aboard. By 11am we were anchored.

March 15th 1865

Got my discharge by strategy – and considered it a very good thing. The Captain had been unable to find a cargo and had therefore decided to take ballast to Hong Kong. I had had a miserable time of the passage and therefore thought it much better to stay in a strange land with neither money nor friends than undertake another passage in such circumstances.

March 17th 1865

Commenced work as Steward of the Aldrich House – the biggest Hotel on the Islands – kept by a German, Mr Kirchoff.

March 26th 1865 (Sunday)

Visited the Church of the Catholic Mission, Fort Street. The service was conducted in the Hawaiian language and I found there at their devotions, many male and female natives, and even Chinamen, so powerful is the effect of the few French Emigrants who established this place of worship. After the service I went into the schoolroom under the church where I saw about forty children, all natives, singing English Sunday School songs from the music. Apart from one Englishman, the teachers were all foreigners. The manner, behaviour and general conduct of the pupils was truly exemplary. Many an English class of Sunday School children at home might have benefited by the example of these poor semi barbarian Kanaka children.

In the afternoon I visited the Native Church, established by an American Missionary enterprise. Here, seated on rude benches, were about 200 natives, all listening with rapt attention to the words of Holy Writ expounded by their minister.

|

| Kawaiaho Church—First Native Church in Honolulu (Northern California, Oregon, and the Sandwich Islands) |

In the afternoon I visited the Native Church, established by an American Missionary enterprise. Here, seated on rude benches, were about 200 natives, all listening with rapt attention to the words of Holy Writ expounded by their minister.

April 26th 1865

.jpg/760px-Raising_of_American_flag_at_Iolani_Palace_with_US_Marines_in_the_foreground_(detailed).jpg) |

| US Marines raising of the US flag at the Iolani Palace in 1898 (Bernice P Bishop Museum via Wikipedia) |

The large hall, temporarily fitted up for the occasion in the grounds of the palace, was beautifully decorated with a splendid variety of native flowers and rare exotics. Around the building were hung, in very nice style, the flags of many nations – the British and American occupying the most prominent positions. The orchestra was very limited in number, there only being three professional musicians on the Islands. Nevertheless they discoursed some very good dance music.

|

| King Kamehameha V in 1865 by Charles L. Weed (from the Bernice P. Bishop Museum via Wikimedia Commons) |

His Majesty the King, with the wife of his Prime Minister22, opened the ball. During the ball I observed the Captain of the Russian ship in many evolutions of the waltz with the Princess Victoria, and Mr Synge, H Bell's Consul, with Her Majesty, Queen Emma. The various officers of the two vessels in whose honour the ball was given, in dancing with the various ladies present, were not slow to avail themselves of the opportunity to display the usual English clumsiness.

|

| Charles Beresford c1880 – still youthful but by then Captain of the gunboat, HMS Condor (Punch) |

Many a gay young midshipman, among them Lord Charles Beresford [who had joined the Navy at 13 and was then 19], disported gaily with stout Hawaiian matrons. Dark skinned young ladies, wearing their most fascinating glances, rivalled each other in attention to their fair skinned partners.

The supper table was most superb in all its arrangements and literally groaned beneath the weight of delicious and beautiful tropical fruits – pineapples, oranges and bananas were piled up in splendid silver and crystal vases. I had the distinguished honour of drinking a glass of "The Good Rhine Wine" from the King's own goblet which displayed the Royal Arms set in precious stones.

April 30th 1865

In the evening I attended service at the Presbyterian Church and heard a very excellent discourse by Rev Mr Corwyn, an American minister of some note here.

May 1st 1865

May 1st 1865

|

| General Lee surrenders to General Grant |

The news of the surrender of General Lee reached here from California [it took three weeks to reach Honolulu from Appomattox]. The American Consul at once hoisted his Stars and Stripes and issued a placard inviting American residents to attend Divine Service at once, returning thanks to the Giver of all Good for this signal victory. In the afternoon there was a grand procession and in the evening the town was most resplendent with illuminations.

May 4th 1865

Met two of my fellow passengers from the Robert Lowe – Reddish from Lower California and Burton from Victoria.

May 8th 1865

|

| Assassination of Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theater, 14 April 1865, (Currier & Ives, 1865. via Wikimedia) |

The news of the assassination of President Lincoln reached us by way of the ship D C Murray from San Francisco. Within two hours, Honolulu was completely draped in mourning and the various resident foreign consuls at once lowered their national ensigns to half-mast.

The indignation of Union men was so great at the atrocity of the murder that they were ready to annihilate in a very short time any person on the Island who evinced any signs of satisfaction. From the San Franciscan papers we see that that City had suffered an almost irreparable loss and this was the most important crisis the "Great Republic" had ever seen.

|

| This is the Spanish Ironclad, Numancia – but I've forgotten why I put it here! |

Something of the Hawaiian or Sandwich Isles23.

The Islands are situated on the great highway of commerce between California and China, India, Japan and many Islands of the Pacific. There are twelve islands, four of which are mere rocks. The other eight have the following names and areas in square miles:

| Island | Area | |||

| Hawaii | 4000 | |||

| Maui | 620 | |||

| Kahoolawe | 60 | |||

| Lanai | 100 | |||

| Molokai | 90 | |||

| Oahu | 500 | |||

| Kauhai | 500 | |||

| Niihau | 90 | |||

According to a series of native traditions transmitted through a long line of chiefs, and other conclusive evidence, Europeans, probably Spaniards, visited these islands over two centuries previous to their re-discovery by Captain Cook.

In one of these traditions24 mention is made of a large vessel, named by the natives Konalihoa, visiting there thirteen generations of Hawaiian Kings anterior [i.e. prior] to the visit of the great English Navigator. By some accident this vessel was dashed to pieces by the surf upon the rocks and made a total wreck. The Captain and a white woman, said to be his sister, were the only persons saved. These, being well received and hospitable treated, became content to form connections with the Hawaiians, from whom a mixed and lighter-complexioned race has sprung and from which a large number of chiefs are said to be descended.

|

| The death of Captain Cook by Johann Zoffany (The National Maritime Museum via Wikimedia) |

In March 1820 the first Missionaries (American) arrived there from Boston in the ship "Thaddeus" accompanied by a printer, a physician, a farmer and a mechanic. All had families with them and their wives were the first civilized women who landed on the Islands.

To the labours of these and others equally in earnest, the natives are largely indebted for the amount of civilization they now enjoy.

The Russian Discovery Ship "Rurik" was the first Man of War that ever entered the Harbour. This happened on Nov 21st 1816 [for a record of the Rurik’s visit see http://mauiwebdesigns.com/Hawaii/HawaiiHistory/arussianvisitskamehemeha.htm]

The Captain presented King Kamehameha 1st with a couple of brass field pieces and at the departure of the Russian ship in the following December national salutes were exchanged for the first time in these islands.

On Aug 11th 1822 the first Christian marriage between converted natives was solemnized. In the same year the first experiments in printing were made.

In 1824 the last heathen sacrifice was offered.

There are three seaports on the Islands visited every year by whalers. They are Honolulu on Oahu, Lahiana on Maui and Hilo on Hawaii.

|

| The view of the hill from Nuuanu Valley ('Sandwich Island Notes', Geo Washington Bates) |

Punchbowl Hill on Hawaii – the national fort at Honolulu situated about a mile out of town – is an old crater, many years silent, mounting some very heavy guns. It is an interesting sight to see a salute fired from its summit on a gala day or on the occasion of the arrival of any man of war in the Harbour. The flash and smoke is succeeded by the heavy boom of the guns and the flags of the Nations represented are saluted.

It was on the large plain island, at the foot of this hill, that I picked up a human skull and, as there are a great number lying round and as tradition tells us there was a great battle fought there some hundreds of years ago, it is not at all improbable that the pate [head] once belonged to some native who fell in the contest.

|

| An engraving pasted in Henry Taylor's Journal 26 |

The most prominent headland of Oahu is Diamond Head, situated 4½ miles from Honolulu.

|

| Diamond Head now (Wikipedia) |

| |

| Diamond Head The Crater (Wikipedia) |

Often parties will ride or walk from the city and scramble up its side to gain the glorious view that is presented to the eye on every side. On a clear day several of the adjoining islands can be distinctly seen, though at a distance of some 80 or 100 miles.

Returning from Diamond Head you may pass through the pretty little village of Waikiki and here get a native boy to run up a cocoa tree and throw you down half a dozen nuts. You could stop a few minutes in a native hut where you will be met with a pleasant aloha (love to you) their universal salutation of farewell. Or you could rest yourself a while on the clean, cool straw matting spread on the earthen floor and, if you smoke, take a whiff of the native's pipe, which is generally handed round to all visitors, whether native or foreign.

The plain, which lies between Waikiki and Honolulu, is the great playground of the Oahu and, on holidays and Saturday evenings, it is one of the prettiest sights on the Islands. There all the horse racing is done and there the natives who can raise a dollar at the weekend, or who have horse of their own, go and gallop about to their heart's content, until dark.

A sailor, when he goes ashore, is bound at the earliest opportunity, to find himself seated on a native horse for a ride and, as sure as he does so, almost as sure will his experience will teach him, that he is arrested and taken to the Fort (used as a prison) for fast riding and fined five dollars. This being one of the principal sources of Revenue, the Fort is often called the "Sandwich Island Mint" on account of the number of $5 pieces coined from poor Jack every time an opportunity offers [itself]. (A resident can ride as fast as he pleases without running any risk whatever).

Two thirds of the police are native, the balance are of foreign birth.

|

| An engraving pasted in Henry Taylor's Journal |

At 4pm on Saturday all business is suspended throughout the town and then commences the fun. It is a merry sight to see a party of native women riding through the town, sitting on their horses, as all ladies sat, before side saddles were invented, their bright Kiheis flowing on each side of their horses, their hats jauntingly set on their heads, or in their place, a beautiful wreath of fresh flowers giving you their pleasant alohas as they pass.

The Kihei is a strip of bright coloured print some 4 or 5 yards long and about a yard wide which they take on their arm (without disturbing their dress which is held with a loose girdle when ready to mount) wind it around their waist and, by a magical process, enveloping their limbs, leaving the end to float to the breeze on either side. The ease and grace with which they mount and manage their horses and their perfectly chaste and comfortable riding habit, would excite the envy of many of their fairer-complexioned visitors who love this healthy and invigorating exercise.

|

| The Pali Precipice in 1948 (Flickr, Tractatus) |

Nuuanu Valley for several miles is one of the pleasantest rides out of town. It ascends gradually until it reaches the height of 1100 feet to the famous precipice (called the Palli) where Kamehameha I first drove the rebellious Oahuams off in former times.

A few miles up this valley the scenery is very fine – turn round and you have a splendid view of the town and harbour. On each side, towering to a height of 2000 feet, you have the large mountains, their sides covered with verdure, giving you a pleasant contrast to the hot, dusty town you have left behind. Before you have a moment's warning, by a sudden turn in the road, your horse (well accustomed to the place) brings himself to a sudden stop and you to one of the grandest pictures of nature you have ever beheld.

Down beneath you drops the precipice before alluded to the depth of 1100 ft. Before you lies the Ocean and the whole of the windward side of the Island. For miles on each side mountains in one vast chain to the height of over 3000 ft making a grand crescent precipice.

|

| Hawaiians eating Poi (Northern California, Oregon, and the Sandwich Islands, Charles Nordhof) |

On your return to the city you can step again into a native hut (where you are sure to be made welcome) and partake of a little poi.

|

| Calabashes (R S Gilbert) |

Being acquainted with the manner of eating you can make yourself quite at home and, after washing your hands, squat down tailor fashion, dip two fingers into the Calabash containing the mess, give your hand a twist or two to get sufficient poi for a mouthful and swallow it at ease. The Poi is a paste made from the root of a native plant called taro which, when baked and mashed with big stones, forms the chief and most certainly indispensable food of the natives. Occasionally they vary their diet by using raw fish which they eat with salt only.

|

| An engraving pasted in Henry Taylor's Journal |

They are very fond of the amusement of surf riding which, though a source of recreation to them, is a grand feat in the eyes of foreigners. To attempt it most people would regard as a desire to commit suicide.

Resumé

June 26th 1865

Shipped as Cook and Steward of the Hawaiian Bark “Arctic”27 Capt Hammond for San Francisco.

July 4th 1865

Participated in a great American Festival here, given by the American residents here, to which the people of every nation at present residing on the Island were invited.

July 11th 1865

Rode to the Palli and back on horseback.

July 12th 1865

Bought $45 worth of bananas, pineapples and goldfish intending to dispose of them to a great advantage in California.

July 13th 1865

Pilot took us out of Honolulu Harbour at 2pm and at 4pm left us at sea with a good stiff breeze on our quarter.

August 11th 1865

After a succession of head winds and calms (during which my fruit all spoiled and my goldfish died) we sighted the heads of the harbour of San Francisco. At 5pm pilot came aboard, at 9pm entered the Golden Gate and at 12pm anchored at Alcatraz Island.

August 12th 1865

Moored at Mission Street Wharf.

|

| Mission Street Wharf, San Francisco circa 1865 (Library of Congress) |

August 14th 1865

Left the “Arctic”.

August 30th 1865

Commenced work in U.S. Rest28, Clay St and took room with Harper29 in Summer St House kept by an Englishman named Brewster30.

Oct 13th 1865

Experienced a very severe earthquake – in fact the most severe ever felt on this coast. Houses knocked down, windows and walls smashed and cracked, even the great bell of the City Hall was tolled by the vibration of the tower. Quite a panic was created throughout the whole of the State.

Nov 3rd 1865

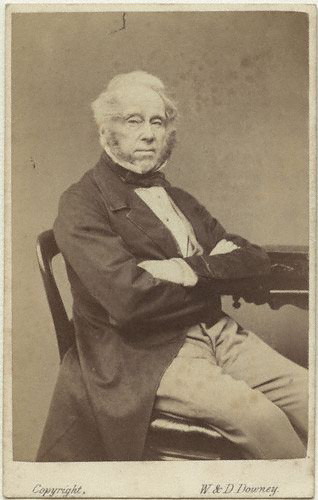

News of the death of Lord Palmerston reached California. Immediately every English house in the city put the British Ensign at half mast.

| Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (1784-1865) British Prime Minister, 1858-1865 and 1859-1865 |

Nov 8th 1865

Left the U.S. Rest

Nov 9th 1865

Saw Miss Emily Thorne of the Theatre Royal, Manchester, at the Academy of Music in “Unequal Match”.

Nov 13th 1865

Took passage with Harper and Brashears31 in the Barque “Harminia”32, Captain Shoemaker for Valparaíso, near Santiago, Chile.

Nov 15th 1865

Sailed at noon

Dec 15th 1865

Crossed the Equator

Dec 17th 1865

|

| Porpoise (porcus marinus) (Marine mammals of the north-western coast of North America) |

One of our passengers, Mr Hudson, harpooned a large porpoise and the next morning had breakfast of it and a very palatable dish it was.

Dec 24th 1865 – Christmas Eve

Another Christmas from home, and at sea too – though under the circumstances we did very well. The Captain supplied all hands with a good glass of whiskey punch each – one of the cabin passengers (the Count as we called him) – had a dozen Chinese lanterns and, as we were laying becalmed, we hung them up amidships. We had some good banjo playing by Mr Josh Mintary and, as the passengers numbered about 60, we managed to have a pretty good time. “John Brown”, “Marching through Georgia”, “Just before the Battle Mother”, “When Johnny comes marching home” and other popular American songs had each a turn in the evening’s entertainment and, had King Neptune been in the immediate neighbourhood of our vessel at the time he would in all probability have joined us and said we were the jolliest ship’s company that ever crossed his path on a Christmas Eve.

Dec 25th 1865

This has been emphatically a “Feast day” with us. Our usual bill of fare was rice or mush – with coffee for breakfast – salt beef and potatoes for dinner and hash and tea for supper. Today we had a good dose of fresh pork, cake and pie each.

Dec 31st 1865

As we were lying becalmed today a large shark with his pilot fish was seen playing round the stern of the ship. Mr Hudson got his harpoon at once and threw it into the very heart of the great brute. With some difficulty we hoisted him on deck and found he measured 6 ft 4 in long. We were all astonished at the extraordinary tenacity of life the creature possessed for, after being disembowelled and “curtailed” he exhibited signs of a evident desire to return to his native element. After his head was cut off – and though it seems incredible – whilst the process of cutting out his backbone was going on he made one final effort that sent the position of his carcase (possessing the most life) several feet along the deck.

At midnight, as usual on passenger ships at sea on New Year’s Eve, we had a great noise. Every article in the ship capable of being turned into an instrument of discord, from the Captain’s speaking trumpet to the cook’s frying pan was brought into requisition to bid farewell to the old year. And, when we retired to bed, two hours of the New Year had passed over our heads.

Jan 1st 1866

Another shark hove33 in sight today. Wishing to try my hand with the harpoon, I persuaded Mr Hudson to let me have a trial at the brute. So I threw it and sent the head of the iron right through the body of the shark. After hauling him on deck we were rather astonished to find in his “bread basket” two wind pipes and the lights from two sheep killed aboard yesterday as well as a pair of old shoes thrown overboard by one of the crew this morning. All [were] in a state of indigestion and perfectly recognizable. I saved a portion of his backbone.

Jan 27th 1866

|

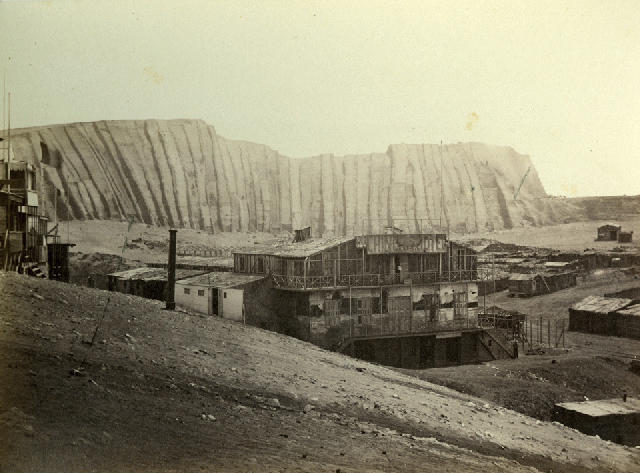

Tomé, near Concepcion in the 1860s (Chile Ilustrado, Recaredo Santos Tornero) |

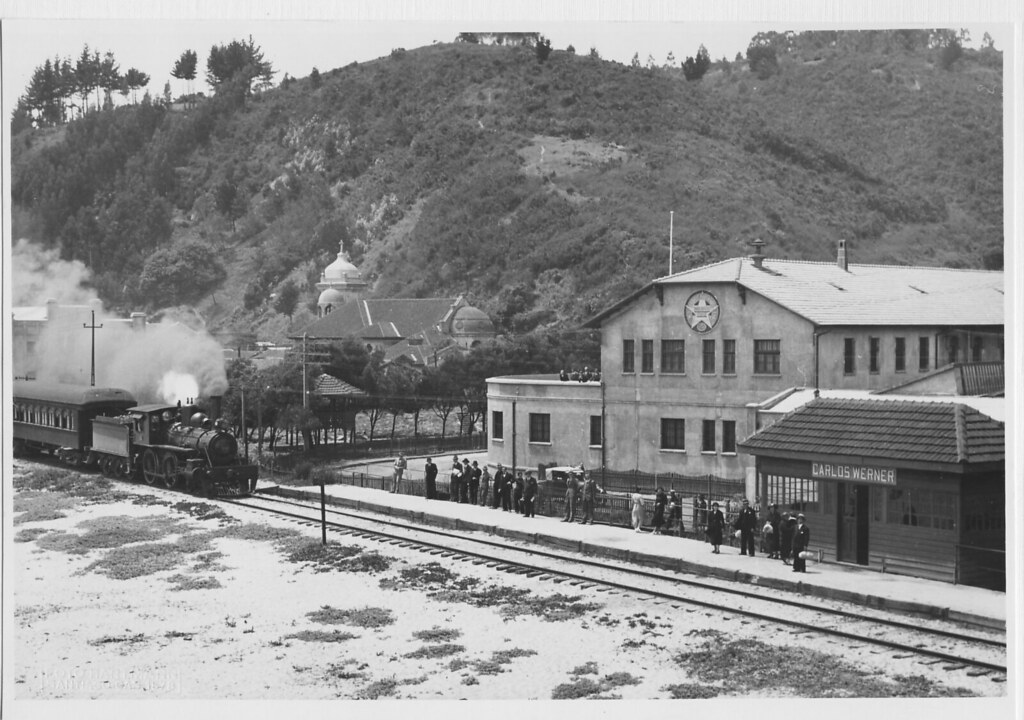

Sighted land at 8am and anchored in the Bay of Tomé at 1pm in Chile 7 miles from Talcahauno. Soon after our arrival the customs house officers came aboard and, on being informed that we were bound for Valparaíso the adjacent port, they told our Captain that the Spanish fleet was then blockading the place. Consequentially we should not attempt to enter. This was what we could expect as the news of the declaration of war between Spain and Chile had reached California two days before our sailing.

La estación Carlos Werner, Tomé in 1916 (conce_antiguo, Flickr)

|

|

| Tomé, 2007 (Nellorolleri, Wikimedia) |

The Captain decided to discharge the passengers in Tomé. Although very much discouraged at the prospect before us we went ashore and found a miserable little one-horse town composed of a number of one-story mud buildings with about a dozen of its inhabitants able to speak English. There are no wharves here for the vessels to haul alongside of. All the cargoes are conveyed to and from the ships in large launches pulled by the native labourers called peones. We found 12 vessels in the bay, 9 of which were under the English Flag.

|

| A Carreto ( Santa Ana Public Library) |

|

| A Chilean Ox-team with driver on board (H Willis Baxley, 1865) |

The driver of the above-mentioned singular vehicles walks ahead of his oxen with a long wand or stick and administers continual chastisement.

Jan 30th 1866

| Portales de la plaza, Concepcion, in the 1860s (Chile ilustrado, Recaredo Santos Tornero) |

Hearing of some gold mines situated about two miles from Tomé, Harper and I decided to try them. Accordingly we took the stage to Concepción – a distance of 21 miles. This was really a delightful ride – saving only the dust. The scenery on every side was most magnificent from sea shore to fearful precipices (caused by earthquakes which are very common in this country). Thence to some little settlement – through groves of trees up hill and down hill.

|

| The old cathedral in Concepcion – destroyed by an earthquake in 1910(Wikimedia) |

Arrived at 2.30pm and found quite an extensive city containing some 12,000 inhabitants and quite a number of large, respectable-looking buildings. The cathedral is indeed a fine specimen of architecture and the interior is splendidly decorated. The Plaza, containing a very beautiful iron fountain, is a great ornament to the city and is much used by the inhabitants as a resort for evening promenading.

I also visited several other churches and was much astonished at their appearance. The natives are without exception Roman Catholics. Though they all profess the faith, they are most inconsistent in their daily life and dealings.

The interiors of these churches are very handsomely decorated. The altars are composed of workmanship of the costliest description and every one contains a wax image of the Virgin Mary. These dolls are beautifully attired – some in silks, some in satins – but all wear crinoline or something that answers the same purpose. The majority of them wear earrings, brooches and even rings on their fingers.

There are no seats in the churches the poor deluded devotees kneel on a cold stone floor during the whole service.The ladies of the country, when going to church, carry a handsomely embroidered cloth whereon to kneel.

We staid at the Hotel de Commercis34 kept by a Mr Derbyshire, a Manchester man.

Jan 31st 1866

|

| Coronel, Chile (memoriachilena, date unknown) |

At Bodega35 we were joined by Mr and Mrs Wright from London. Mr Wright is a man who has been travelling in Chile for some years as a photographic artist. He is a man of considerable intelligence and gave us a great deal of useful information concerning the Country. This proved of some service to us. On our arrival at Coronel they invited us, during our stay, to make our home with them. As we only intended staying one night, we accepted the kind invitation.

|

| The area around Concepcion based on a map by Lebour & Mundle The map appeared in an 1870 article about coal-bearing rocks. |

This is another small Spanish town – a very miserable little place containing not one building of any other materials than wood and a number of native huts formed of very rough branches of trees roofed with grass.

The natives in these rude habitations are quite content without any article of furniture. The floor is their squatting ground and their bed. In the centre of the hut they build a small wood fire and do all their cooking by it.

In civilization the lower classes in around the small towns are not, I consider, one iota superior to the Chinook Indians of Vancouver Island and Puget Sound.

Feb 1st 1866

|

| A former mine and tiera colorado in Lota, Chile, (Rene Robles, Flickr) |

Five of us, viz Harper, Brashears, Heinmann, Bauer and myself, shouldered our blankets and started for the expected Eldorado – afoot in right good earnest – and the same evening arrived in Lota, another small town, but possessing some good lucrative coal mines and a very extensive copper ore refinery. A very considerable quantity of the ore from this place is shipped to England – principally to Swansea.

Staid at the house of Mrs George Lee – a Chilean Señora married to an American. Here we were very well treated at a moderate charge.

Feb 2nd 1866

Started again at 5am and after a very rough walk of over 30 miles, we arrived at a small native ranch – more than eight miles from any other human habitation.

Here we found the Señor, his wife and children. I was chosen as interpreter, though my knowledge of Spanish was very limited indeed. I was likely to remember however my first attempt at a sentence. It was this: “Buenos dias Señor, cinquo36 hombres, muchos hambre, caro pan y queso en jueves tambien” which, being literally translated into English, is simply this: “Good day sir, five men very hungry want bread and cheese or eggs”.

|

| Henry Taylor's Journal – preparing a meal in Región del Biobío |

We could get neither bread not cheese, but the Señora, noticing I presume, that our faces betrayed our hunger, pointed to some chickens. We did not need any further pressing, but one of the party felled six of the young hens. Whilst some went to kindle a fire the rest of us strolled onto the patch of ground the worthy Señor cultivated and were most agreeably surprised to find growing plenty of potatoes and onions. We gathered what we thought would be sufficient for a good mess, and as we had a professional cook with us (my old friend Brashears) we soon had a good supper under way. After partaking of the same, and smoking a pipe, we began to look round for a place to sleep but, as the house (if it may so be called) only contained one apartment and we had already seen nine of the family, we decided to sleep outside. Rolling ourselves up in our blankets, tired, weary and footsore, we soon fell asleep – but not for a very long period as the fleas and mosquitoes were so numerous. The most weary of us could not get a wink of sleep.

For an hour or so we stood it like heroes, but patience is only human. We, as a last resort, got up, made a good large fire and resolved to trust to the smoke emanating from that, and our tobacco pipes, to keep the enemy off. We succeeded to some extent but, with the mosquitoes, some were smart enough to stow themselves in our clothing and blankets, where our attempt to drive them away had no effect whatever.

However, nature had to give way at last and we slumbered, perhaps for fifteen or twenty minutes. Then the clouds, which had been looking rather gloomy the whole evening, poured down upon us such a deluge as to wet our blankets through in a very short time. All we could do was to grin and bear it as we had no available place of shelter.

Early in the morning, our host was astir and getting ready a repetition of the previous evening’s supper. We ate it and off we started again but, on account of the slippery state of the ground, we were unable to get along as well as before the rain.

|

| Chilean miners in 1855 (Jay Monaghan) |

About noon we got a horse each and rode the rest of the day and the whole of the following day before we arrived at the Romars37 – the mining settlement of our destination which was called “Los Minos de los Noches”38 or “The Mines of the Night”.

Here we met with several old Californian miners, doing a little here and there, but they told us we would in all probability be disappointed as there was only one company on the creek (Pas Diablo)39 making more than grub. At this intelligence our ardour was somewhat damped – but we determined on a trial.

We passed the night in a miserable brush shanty – with any quantity of fleas and mosquitoes for company.

Feb 4th 1866

Four of us walked over to the creek this morning and inspected several of the working claims. We also, by permission of the owners, panned out several pans on the various claims but the results were anything but encouraging.

Feb 5th 1866

Early in the morning Harper and Heinmann set out for Arowco40 to purchase tools and some little necessaries we could not procure at the Romars.

Feb 6th 1866

Commenced work on the Big River41 but, after damming the stream, setting up sluice boxes and in fact working like niggers for eight days, we decided to give up as we had only taken about 20 cents worth of gold in the whole time.

Feb 15th 1866

Harper, Brashears and myself started back afoot, very much discouraged and very low in pocket. This evening we “camped out” as we were too tired to proceed any further, though we knew there was a ranch about five miles on. We slept better than usual and, next morning at about 6 o’clock we had the satisfaction of seeing smoke issuing above the trees on the lower side of the hill we were crossing. We staid awhile and made hearty breakfast off bread and cheese and again pursued our journey. It was indeed weary work – all our path lay through very thick woods up and down hill. The days were very hot indeed and the streams from which we quenched our thirst “few and far between”. We did occasionally meet a Señor on horseback and we were glad to return his greeting. We were not inquisitive enough to enquire his destination though we had many surmises as to where any Christian (except ourselves of course) could possibly be going.

Feb 17th 1866

In the evening we arrived at Lota again and staid at a native “Casa de Trata” [House of Slaves].

Feb 24th 1866

After having spent a week here, endeavouring by every exertion to obtain some kind of employment, I heard of a vessel going to Coquimbo and asked the Captain for a chance to work my passage. The ship was lying at Coronel so I walked over and the same evening I had the pleasure of stepping aboard the fine American ship “Duchesse de Orleans”42.

Feb 26th 1866

|

The Port of Coquimbo in the 1860s (Chile ilustrado, Recaredo Santos Tornero) |

Sailed at 10am and after a passage of five days arrived at Coquimbo, a distance of 480 miles from Coronel. During the passage, of course, I stood my watch night and day. Never can I forget those weary two hours of a “lookout” on the topgallant forecastle [the uppermost exposed deck above the forecastle] and what numerous reflections would fill my brain. I cursed my folly for leaving a good berth in California to go to a country of whose manners, customs, people or climate I knew nothing. Above every other regret stood predominant my cursed folly at home in being so unsettled and in cultivating my wondering disposition instead of checking it. I know of no one so much to blame as myself. I have been my “greatest enemy”. I had always at home an opportunity of being at least in a respectable position, both as to business and society. But, since leaving England, I have been obliged to take menial situations and never been recognized by any person in a superior position to myself. The same evening of our arrival at Coquimbo I went ashore and staid at Philip’s Boarding House.

March 5th 1866

|

| Coquimbo Bay in 2006 |

Went aboard the Pacific Steam Navigation Company’s Steam Ship “San Carlos”43 and obtained employment. Sailed the same day and called at the following ports:

| March | 9 | Papudo | Chile | ||

| " | 9 | Tongoy | " | ||

| " | 12 | Coquimbo | " | ||

| " | 13 | Huasco | " | ||

| " | 13 | Caldera | " | ||

| " | 13 | Carrizal | " | ||

| " | 14 | Chanara | " | ||

| " | 17 | Iquique | " | ||

| " | 17 | Mejillones | " | ||

| " | 17 | Pisajua | Bolivia44 | ||

| " | 18 | Arica | " | ||

| " | 18 | Ilo | " | ||

| " | 19 | Islay | " | ||

| " | 20 | Chala | " | ||

| " | 21 | Pisco | Peru | ||

| " | 21 | Chinchahalaos | " | ||

| " | 22 | Callao | " |

Walked over to the copper mines of the English Company at Guacan45 where I found quite a Welsh settlement. I enquired if there was any chance of employment in any capacity whatever and was answered in the negative. The probability is that, had I been Welsh instead of English, I would have obtained employment.

March 9th 1866

At most of these ports I went ashore with the storekeeper – but what I saw is not worth mention. The majority of ports in Chile are supported by copper and saltpetre mines. In Bolivia how and by what they exist, goodness only knows. In the Peruvian ports the natives cultivate fruit and manufacture wine and pisco [national drink of Chile and Peru]. The profits on the two latter articles are considerable as the demand in Callao is very large.

March 30th 1866, Good Friday

This is the first time I have seen this day noticed since the last one I spent at home. As this is a Catholic country the people make a great deal of the day.; They have processions through the streets and services in the churches.

|

| There are still street processions in Peru as seen in Miroflores, near Lima, on 11 November, 2006 – St Martin's Day |

|

| The yards of square-rigged sailing ships were often cockbilled as an act of mourning. Geoff Hunt drew this sketch of HMS Surprise – yards cockbilled – in memory of Patrick O'Brian |

The vessels lying in the harbour hailing from Catholic countries all have their yards “cock-built”46 from Thursday sunset to Saturday sunrise.

April 8th 1866

Taken sick and the Company’s Doctor sent for to see me. On feeling my pulse and hearing of my symptoms he told me I had fever and ordered me at once to the Lima Hospital47. Here the doctors told me I was suffering from Typhus fever. I was insensible for about a week. Immediately on recovering my consciousness I sent for the Lady Superior (bye the bye, the hospital is in the charge of the French Sisters of Mercy48) and requested her to write a few lines to my Mother and tell her of my position. This she did with an evident degree of pleasure as she saw it would gratify me. She is a very fine woman, the widow of a French count of some note who perished in the Crimean War. She told me she had travelled a good deal in England and spent several months in Manchester and Salford.

| A courtyard in Hospital San André, Lima (Photograph by Santiago Stucchi Portocarreroy) |

[Santiago has written a History of Hospital San André including superb photographs]

| Hospital San Bartomolé, Lima (Wikimedia) |

April 28th 1866

The wife of the President of Peru visited the Hospital today and presented every patient (about 850) with one real [a 25-cent Peruvian coin] each.

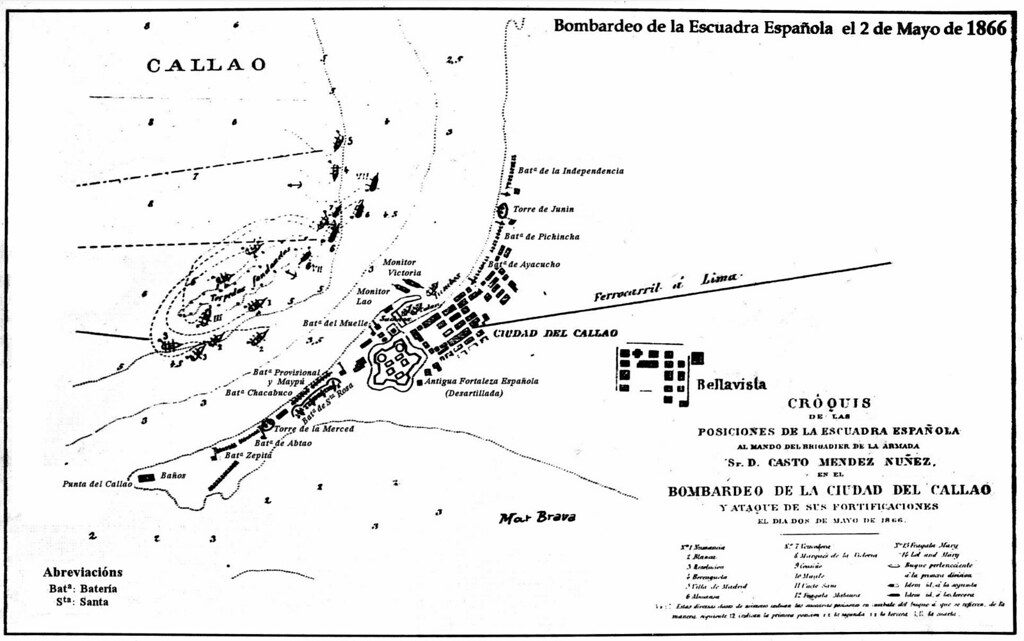

May 2nd 48 1866

|

| The ironclad Numancia, flagship of the Spanish fleet (Wikimedia) |

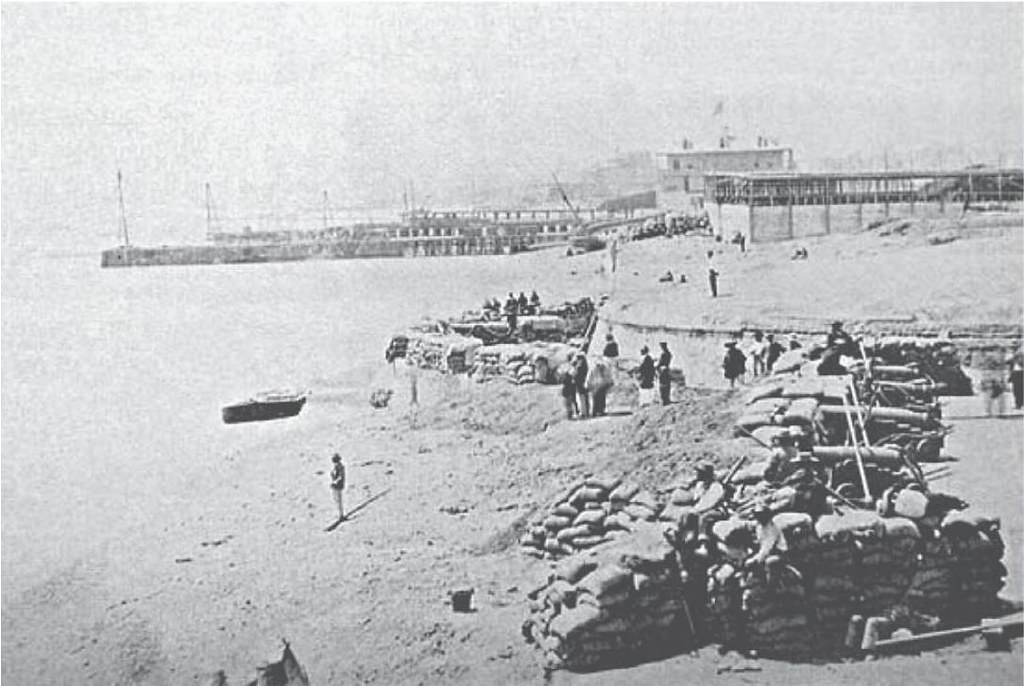

The Spaniards have been threatening to bombard the principal ports of Chile and Peru for some time past and today they are carrying out their threat as far as Callao is concerned. We can hear every gun and are wondering whether or not they will be successful in destroying the town. I myself am feeling rather uneasy as I left my personal property at my Boarding House there not anticipating an attack so soon as this.

May 4th 1866

We have now 32 of the sufferers from Callao in our ward. The majority of them were injured by a large bombshell thrown by the Spanish Admiral's ship onto the beach near Santa Rosa Battery. The place is covered with small stones weighing from an ounce to two pounds each. The effects were fearful, proving in many cases instantly fatal.

Two of the poor fellows died here this morning close in sight of the bed where I lay. It has been necessary to amputate the limbs of some of them. Only this morning I was witness of the operation being performed on two poor soldiers, mortification having threatened their legs.

May 5th 1866

Two more carried to their last home today, one from the very next bed to my own – making the fourth who has died on it during my short stay here.

May 7th 1866

The Doctor pronounced me sufficiently recovered this morning to leave the hospital and, strange as it may appear, I was reluctant to go. The scenes daily witnessed by every patient in that charitable and truly noble institution are repugnant to the feelings of the most hardened and inhuman. Yet one gets accustomed to it, and when one leaves, one is sure to miss the morning and evening visits of the “Madre” [mother or matron] and her shrill monotonous voice repeating the threadbare prayer in Spanish.

|

| Lima Cathedral, c1865 (Mánuel A Fuentes) |

|

| Lima Cathedral, 2006 |

During the afternoon (though feeling anything but well enough to walk much) I had an opportunity of seeing the far-famed cathedral and churches of Lima. The former is built in the Plaza or Public Square and it is, without exception, the grandest and most imposing edifice used for religious purposes that I have ever seen – not excepting by any means St Paul’s in London.

|

| Iglesia San Francisco, Lima c1865 (Mánuel A Fuentes) |

|

| Iglesia San Francisco, Lima in 2006 |

The churches are numerous and built in a stout, substantial manner but, at the same time, in a very fanastical shape and style. The bells of some of these places are tolling incessantly from sunrise to sunset.

|

| Calle de Los Judios Lima c1865 (Mánuel A Fuentes) |

The city is in itself a goodly-sized one and a great commercial depot for the whole of the Peruvian and Chilean coast.

I left Lima by the evening train for Callao and, on my arrival there, found the town in a state of great commotion. Only a few stores are open and all the movable goods and merchandise have been removed from them to places beyond gunshot – chiefly to Buena Vista, a small village on the road to Lima. The Spanish fleet, having met with a warmer reception than they anticipated, after 4½ hours hard shooting, retired to the entrance of the bay, there to repair damages. At the time of my return to Callao a renewal of the attack was expected every hour. The town bears evidence, in a very substantial manner, of a recent bombardment. The largest and principal buildings are all more or less damaged but, as the majority of the houses are built of mud or light wooden framework, the shell and shot passed through them as a pistol ball would through stiff paper leaving only an aperture the size of the missile itself.

Most of the inhabitants, I find, have gone aboard the vessels lying in the bay, there to await the end of the hostilities. What few people were left in town were kept in a dreadful state of suspense until. . .

May 9th 1866

. . .when the Spanish Squadron withdrew and the various foreign consuls at once notified the public that the blockade was rased. In a few days the town resumed its former business aspect, but the hostile encounter had produced stagnation amongst the tradesmen and people of business generally, from which it will take some time to recover.

The general opinion here seems to be that the Spaniards did not consider their squadron of sufficient size and force to meat [he means mete] out to the Peruvians a most disgraceful chastisement, so the Admiral had decided to retire for a while to recruit [archaic for recover] his strength.

Callao

|

| A Peruvian iron-clad ship in the floating dock at Callao (Illustrated London News, Jan 1867) |

The principal seaport of Peru is not so large or thickly-populated as Lima (though being far superior as a business town) nor can it boast of such handsome buildings as that place.

The Railway Station is a long, plain-looking, two-story building situated on the Mold (as the pier is called). The Railway Company is English as also are most of the employees.

The police are all natives. They wear a sort of military surtout [a close-fitting overcoat] in style somewhat resembling the tunic of dark cloth worn by the Third Manchester Volunteers. They each carry a small carbine which they frequently use without proper discretion. They are of a very bold and courageous disposition, as may be inferred from the fact that they generally combine to the number of five or six to take into custody a single person.

A soldier of the 3rd Manchester

Volunteers in Henry's time

Volunteers in Henry's time

The laws of the country are of a most despotic nature, most especially so in regard to the treatment of Foreign Subjects. A man being arrested on mere suspicion (often at the request of some individual who has a “crow to pluck” with him) is kept under the strictest surveillance in Castel Marta – sometimes for months without being allowed the privilege of an interview with friends, relatives or a legal advisor. When the trial does take place he is neither allowed to be present, nor is he made acquainted with the result thereof for weeks. Money will invariably purchase the freedom of the greatest rascals in the country.

|

| Mariano Ignacio Prado |

The president – Señor Prado49 – is the choice of the Revolutionists of the Fall of 65 and is generally regarded by both the native and foreign inhabitants as the Saviour of Peru.

His policy is of a very energetic nature and has already added much to the commercial resources of the Republic.

The "Compania de Vapors Ingles"50 or "English Company of Steamers" is by far the largest and most important business institution here. They have some 18 to 20 fine steamers – both side-wheel [paddle steamer] and propellers – constantly running between Chile, Peru and Panama. They call at nearly every intermediate port. They have a large establishment at Callao, occupying some acres of ground. Here all the work necessary for carrying on so important and extensive a traffic is executed. Almost every trade has its representative.

The Army of Peru

This resembles to a great extent that of Chile. The soldiers are hungry-looking, dirty, miserable, ignorant and slovenly to a most incredible extent. To see them on an afternoon’s parade you would take them to be the remnants of a starved-out garrison. Their uniforms (if such they may be called) are manufactured from the commonest materials possible and made up without regard to shape or fashion. Withal they ape the manners and airs of their military brethren of more civilized countries and endeavour by every little means to appear gaudy and to make as great a display of jewellery as their limited pay will permit.

|

| A Peruvian soldier and his wife (Library of Congess) |

It is no uncommon sight to see a private with toes peeping out of his dilapidated shoes, his chin dirty from neglect of proper and periodical use of the razor and his hair exhibiting unmistakable evidence of long estrangement from the comb. He may well sport a fancy chain of gilt brass and a “Birmingham gold” ring on his finger.